As a new segment here at The Apartment Woodworker, I will be documenting some of the smaller projects I find interesting and which I think are good for skill-building. I’m not one for CAD, so the focus will be on the (sometimes extremely) limited set of hand tools these projects require. There may be basic cut lists as required, but most of it will be rough dimensions.

This isn’t about teaching people how to woodwork. There is a body of instructional material out there far better than I’m capable of producing. Just Google “Paul Sellers the three joints” and go from there. The goal here is to inspire people to pick up some hand tools and make something, without breaking the bank on a tool collection or materials. So without further ado:

I love sushi (specifically, spicy salmon rolls). I’ve always wanted wood sushi trays (I see them called “geta”). So I recently decided to build a prototype. I like this project because it requires friction-fit dadoes, which are my favorite joint to cut. Mine was built from scraps, so I’ll make more as I have the materials.

As far as first tries without plans, it’s not bad.

It’s true that similar items retail for under $20 each on Amazon.com. But you know what also costs under $20? An eight foot select pine 1x 8 from the home center, and you can get four trays out of a single board. You’ll need some food-safe finish (like butcher block oil) and food-safe glue (like Titebond II), but that’s still about half the cost of paying someone else to make you a set of four.

Use harder, food-safe cutting-board woods if you’d like, but they probably aren’t necessary for the amount of abuse these will take. That having been said, everyone has allergies, so go with whatever food-safe wood works for you. And regardless of wood, I also like to surface plane every board I get from the home center. I have no idea what kind of gunk it’s been exposed to, so I always feel more comfortable with clean fibers showing.

The essential tools for the project are as follows:

- 1/2 and 3/4 chisels, plus mallet

- No. 4 or No. 5 bench plane

- 9-14 TPI Rip cut saw (panel or tenon is fine)

- Combination square and marking knife

- Tape measure

- Sandpaper

- Food-safe glue (I used Titebond II)

- Food-safe finish (I used Goddard’s butcher block oil)

Optional tools (which will make the work easier) are:

- Router plane (any size will do)

- Wide chisel (1″+)

- Shooting board (if you don’t have one, walk away from this project right now and make one)

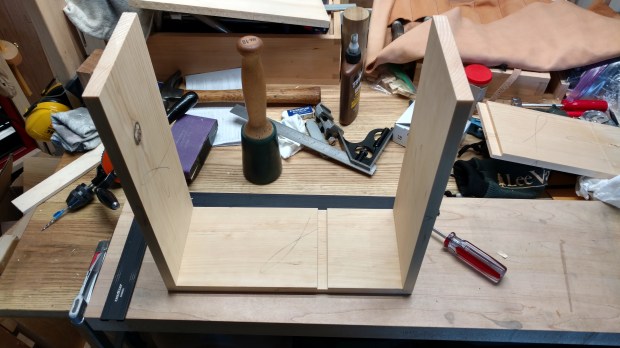

The top is made from a 15″ length of 1×8. The feet are made by ripping a 7.5″ length of 1×8 into thirds and squaring everything up with a bench plane (you need two feet per tray). There is no magic to the height of the feet, but anything between 2″ and 3″ should be fine. For aesthetics, the feet are slightly longer than the top.

There are two dadoes on the underside to accept the feet. Because the top has a 2:1 ratio, for symmetry I started the dados 2x their thickness from the outside edges (in this case, about 1.5″). Each dado is supposed to be 1/4″ depth, but if you’re like me, you always end up deeper because of errant depth chops on the sidewalls. If you have a router plane, awesome. If not, pare the dadoes with a chisel (and go slow, being careful about uniform depth). None of the above measurements are requirements, but I have found that dado depth probably shouldn’t be more than 1/2 the thickness of the top piece.

And be sure to label your parts.

Break the corners everywhere (except where the feet fit in the dadoes) with a plane or sandpaper. A bead of glue on the floor of a friction fit dado is more than enough for a permanent joint. If you need to, drive the feet home with a mallet and a piece of scrap and leave them for an hour. Then lightly sand the top, clean off the dust and finish all over with a thick rub of butcher block oil (the pine will be thirsty). After a wash or two, reapply more butcher block oil to the top face. It should be good for many uses after that. And if you used a PVA glue, it should be dishwasher safe.

And that’s it. Repeat as many times as you like.

Congratulations! You now have practice hand-cutting open dadoes, which you will use in woodworking forever. And the trays are quite multi-purpose, working just as well for cheese and crackers or as coasters.

I hope this has been informative. If not, keep it to yourself.

JPG

![IMG_20160128_204049456[1]](https://theapartmentwoodworker.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/img_20160128_2040494561.jpg?w=620)