In case you didn’t know, every episode of MacGyver is available on Netflix. And I’ve been watching the hell out of it. I recently saw an episode, Season 2; Episode 9, called “Silent World“, where Mac [30-year old spoiler alert!] stops a plot to steal a guided missile with the help of a friend, who is a teacher at a school for the hearing-impaired.

In the episode, the teacher (who is the best-acted character in the episode) has a recurring nightmare that helps identify the perpetrators. The nightmare seems at first like a prophecy, but is decoded as the episode progresses and in fact turns out to be based on her recent experiences. It’s amazing how the human brain works, using dreams to process and catalog the myriad sensory information we receive every day.

So what does this have to do with woodworking? I had been thinking about the design of my new workbench build, which I’d characterize as part Roubo, part Moravian. A bespoke, if not novel, design to utilize the available materials in the most effective way possible.

The “Slab to Frame” ratio is about 2:3.

It turns out, however, that my design is a complete knockoff, being positively Follansbeean. I was reading his blog’s archives and came across the post where he set up his bench in his new workshop (under a tarpaulin). A post published long before I started building my new workbench.

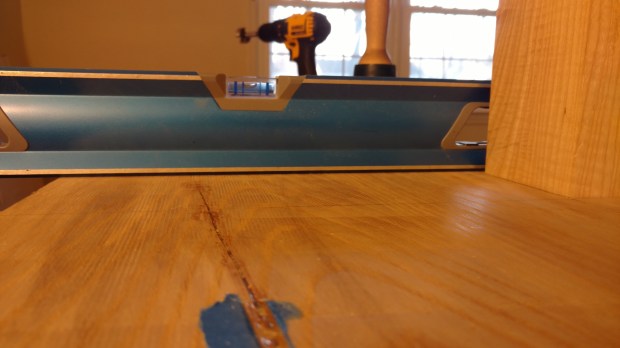

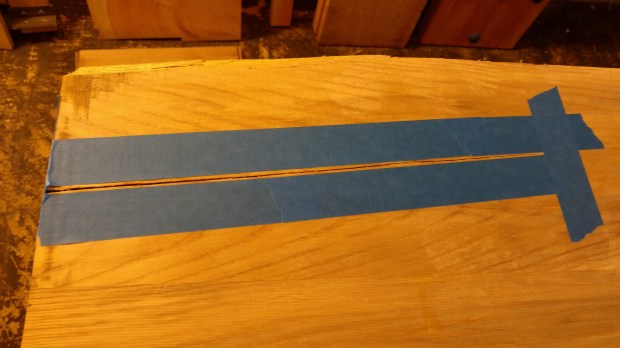

Although my bench won’t have wedged through-tenons on the long stretchers (I’ll drawbore all the stretchers), mine otherwise matches Peter’s pretty closely, right down down to the spacers on which a thinner shelf will sit to extend the benchtop. My design is born out of only having 15″ x 92″ of 16/4 ash for the main slab top, and I would be willing to bet Peter was solving the same problem.

Two stub tenons on the front legs go into the benchtop and keep the slab in place.

Funny how the brain catalogs these things for later use. But now at least I can give the design proper attribution.

JPG