I’m no stranger to angled mortises. But I’ve never done staked furniture before, so when it came time to bore the through mortises into the Roman Workbench slab, I didn’t know what I was getting into. I read and reread the entries in both The Anarchist’s Design Book and Roman Workbenches, and I think I nailed the sight line and resultant angles, but it was still a bit touch and go.

The front two mortises look pretty good.

I should have done a test mortise because, as often happens, the first one is a bit wonky. It’s not quite lined up laterally, and I can tell the rake is off by a few degrees. Not just by eye, but also because it’s the only mortise that had any blowout on the top face. While I can fill in the chipping (and might even paint the top), there is not much I can do about the angle. Luckily, it’s the back right leg, so I won’t see it day to day.

There is always one.

So that means it’s just about time to make the legs. Shaping the tenons without a lathe will be one challenge, but before that, I’ve got to rip down the legs. By hand. Out of 8/4 air dried red oak. At least it will be a workout.

I wish I had a table saw right about now.

Speaking of wishful thinking, it would have been great to know about the Roman Workbench form when I first started woodworking five years ago. This seems like the perfect workbench for getting started in an apartment with a limited set of hand tools. It’s easy to make and straightforward. Hell, you could probably even make the top from a single sheet of 3/4″ plywood ripped four times down the length.

Plus, with an extra cleat on the underside, a Roman Workbench could also go up on saw horses and act like a Japanese-style workbench for added flexibility. And flexibility is the key to apartment woodworking, in my experience.

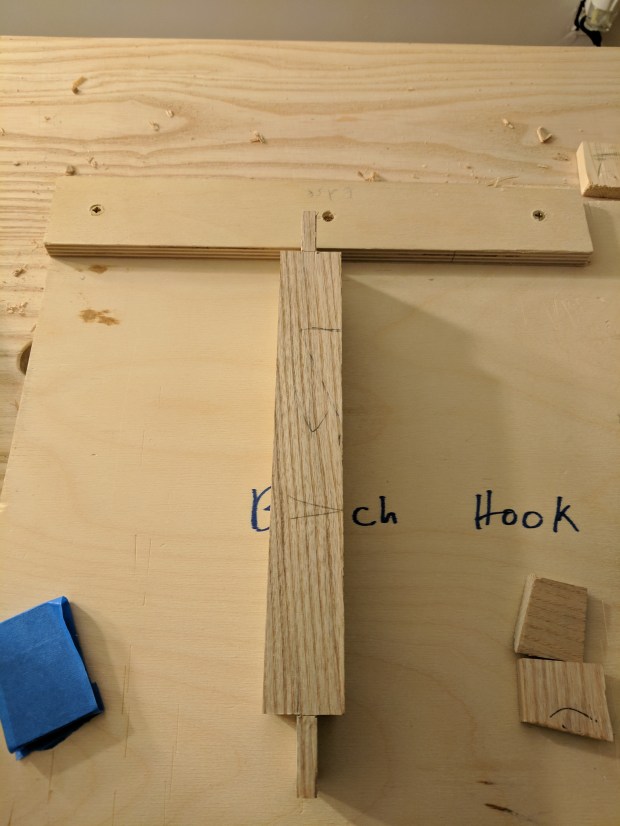

Like this, basically.

Oh well, coulda, woulda, shoulda, right?

JPG