My weekend was somewhat productive.

On Saturday, I set up the temporary workshop at my parents’ house. I even solved the biggest problem with my old workbench: stability. I did so in two ways. First, I screwed the top down to the frame with some 3″ No. 12 screws (no longer just relying just on the friction-fit 3/4″ stub tenons for lateral support). Second, I loaded up the underside of the frame with additional ballast in the form of five-to-six foot lengths of lumber. The net result is a workbench that now weighs about 300 lbs (better known as approximately what a workbench should weigh).

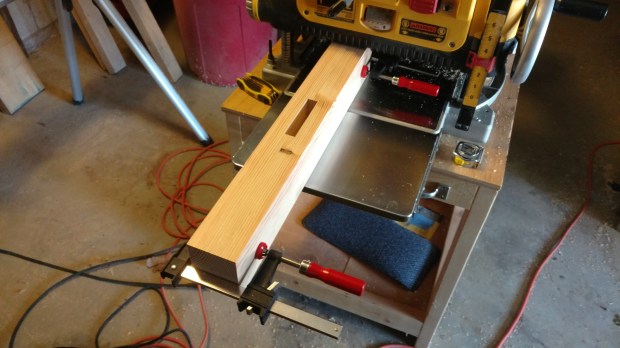

From L to R: 8/4 red oak, 6/4 maple, 8/4 maple, 2×6 Douglas Fir and 2×10 Douglas Fir.

On Sunday, I got right to ripping down almost all of the Douglas Fir 2×10’s that will become the new workbench. Approximately 60 feet of 2×10’s became the following:

- 2 x 4.5 x 72 (times 12, for most of the laminated benchtop)

- 2 x 4.5 x 62 (times 4, for most of the laminated legs once crosscut)

- 2 x 4.5 x 82 (times 2, for the tenons on the laminated legs once crosscut)

The final 82″ of 2×10 (seen below the bench) is the prettiest lumber of all (even with a knot or two) and will become the faces of the front legs and the benchtop. Some of the off-cuts from the 82″ lengths will also go to the strips of the benchtop that form the mortises (more on that below).

To be left out, for a week, to further acclimate.

Four things became apparent during the stock breakdown process.

- I really miss my miter saw. For this build, waste is anathema, and a clean, straight, crosscut is key to ensuring full length. And it’s so much quicker than by hand. my miter saw used to live in my old apartment. I had no idea how much I missed it.

- Even quarter- and rift-sawn lumber has internal stresses. One of the 12 foot lengths of 2×10 (in fact, the clearest and straightest-grain of the batch) split lengthwise along the grain while I was crosscutting it on the miter saw. There was so much energy bound up in the piece that upon splitting a shard of wood shot off the main board and hit me in the eye protection. After cutting around those stresses, the remainder of the piece will become one of the strips that form the mortises on the benchtop.

- I don’t have enough lumber for the entire bench. The plan was for the lumber seen above to be the entire bench, but I don’t think that will work. This should nonetheless get me a 4 x 20 x 72 benchtop and four 4 x 4 legs, and probably the short stretchers. I think another 16 feet of Douglas Fir 2×6 will be plenty for the long stretchers.

- Battery-powered circular saws have limitations. Just ripping the lumber shown above used four full charges of double 20V batteries and three full charges of single 20V batteries. I either need another charger or a corded circular saw.

More than anything, this post has helped me think through exactly how to use the available materials in the most efficient way practicable. I may need one or two more boards, but for about $100, I will have most of a proper workbench.

JPG

![IMG_20160128_204049456[1]](https://theapartmentwoodworker.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/img_20160128_2040494561.jpg?w=620)