I had in my mind a singular vision. A mini workbench, surrounded by a tray, that sat upon an office desk. Like those perpetual motion clacking ball desk toys. But where one could plane small sticks of wood with a block plane in meditative rhythm. The small curls falling gently into a rimmed collection tray to keep things neat.

I could have sworn such a thing existed. Maybe it was advertised in an old Popular Woodworking issue. It might have been Fine Woodworking or WOOD. But it eluded me.

So I made a prototype. And it turned out great!

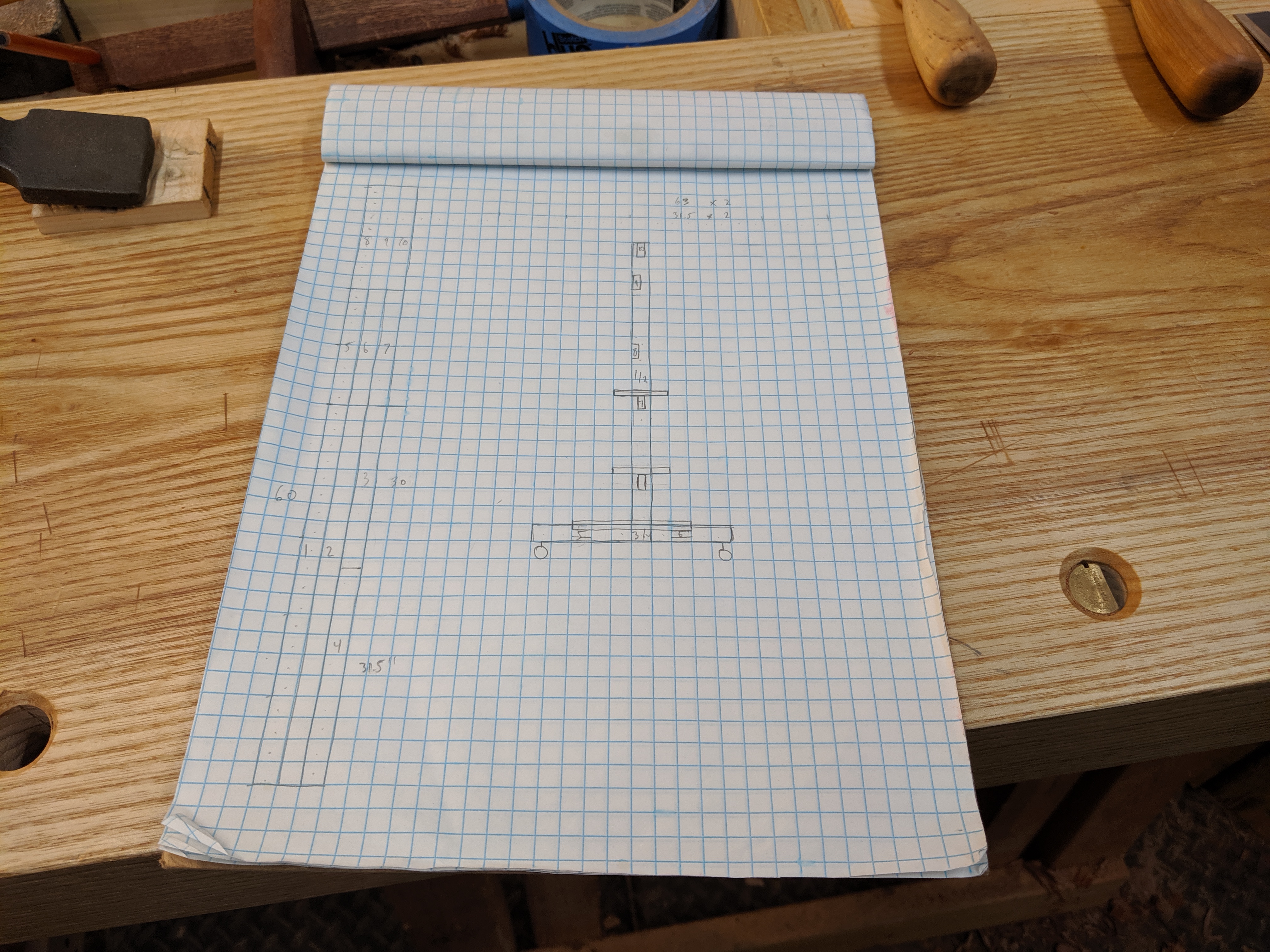

The bench itself is roughly 1:8 scale. The slab is 12 inches long and 3 inches wide. 1/2 inch thickness would have been to scale, but I bumped it up to 7/8 for stiffness. The wing, which functions as both a tool shelf and a shooting board, is about 1 inch wide and 1/4 inch thick. The planing stop is 1/2 inch square. For those who care, the entire setup is 19 x 7 x 3.

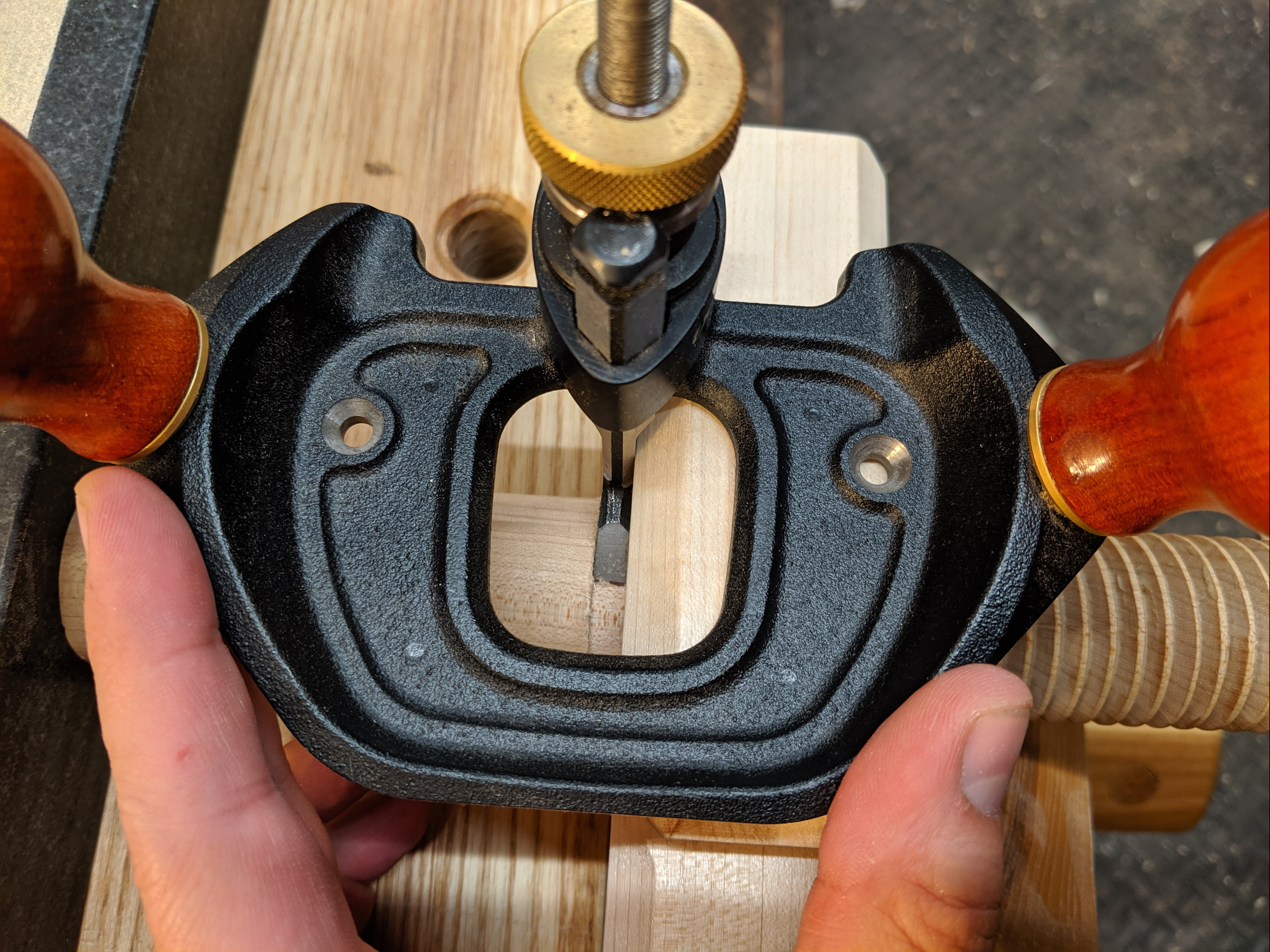

Let’s talk materials for a moment. This is just a prototype, so I used some tight grain Spruce framing lumber from up north. In Vermont, where my parents have a house, you can get stuff that has birdseye pattern and blue streaks but still arrow straight grain. It’s beautiful and a joy to work with.

This stock was a bit more plain, but I think still looks good. The only non-Spruce materials in the piece are the planing stop (red oak) and the base of the tray (1/2 inch birch plywood).

Spruce is rather rigid and dimensionally stable, so a good choice for this.

The workbench legs are 1 1/2 inch x 4 inch x 1 inch posts that are rabbeted (cross grain) into the slab top. The oak planing stop is also rabbeted in. The planing stop actually hides some nails reinforcing the joint between the slab and the front legs. The tool shelf is just brad nailed down to the legs.

To attach the bench to the collection tray, the legs are glued and screwed from the underside of the plywood. The tray itself is banded in 1/2 inch spruce just butt jointed around and glued and nailed on. I stuck on some nonskid furniture pads to the underside so it won’t slide around.

There is admittedly a practical purpose to this piece. There is a step down on the window sill in my office at work. The larger pots overhang the stepdown and it’s unstable without a spacer that’s level with the main sill and fully support the pot. Each spacer needs to be somewhere between 1/2 and 11/16 but the height varies. This will allow me to fine tune some pine 1 x 3/4 spacers on site.

A full size, modern block plane is probably a bit much for this setup. Perhaps I’ll clean up a slightly smaller vintage block plane from the user pile. We’ll see.

When I make a nicer version in mahogany or walnut, I may do a Basic Projects writeup. But for now, the prototype is rather serviceable.

JPG